Your cart is currently empty!

This interview was originally written by Robert Schryer for PMA Magazine.

Founder of Quebec’s fabled Le Studio music studio and recipient of the Order of Canada and an honorary doctorate from Laval University, André Perry has worked with a who’s who of musical icons: John Lennon, Rush, Cat Stevens, The Police, the Bee Gees, Keith Richards, Roberta Flack, David Bowie, and the list goes on. More recently, he is co-founder, with sound engineer extraordinaire René Laflamme, of Fidelio technologies Inc., whose 2xHD recordings (available for purchase here) are known across the world for their combination of musical excellence and sound quality.

It all started humbly. Hailing from a modest background, André left home at age 14, equipped only with a conviction. As he told me in our phone interview*, “I knew exactly what I wanted to do and there was no way anyone could stop me.” Exactly what he wanted to do was music. With that as his North Star, André started working as a busboy in a nightclub to be around bands and, more specifically, observe the drummers. At 17, he formed his own band in which he drummed and sang.

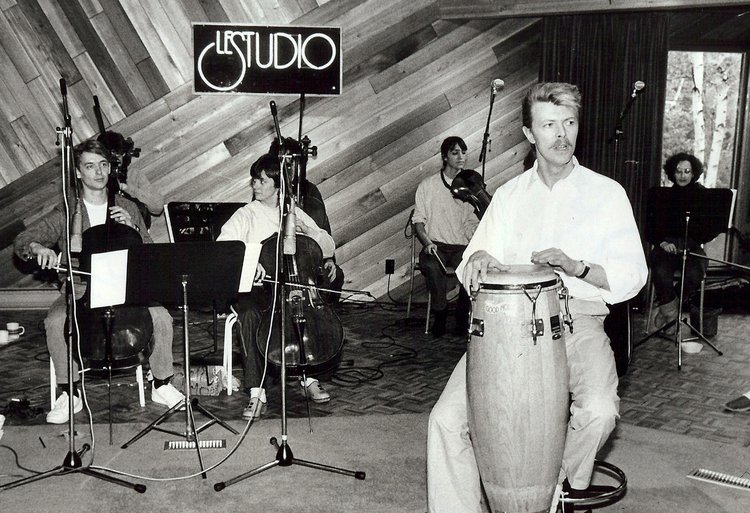

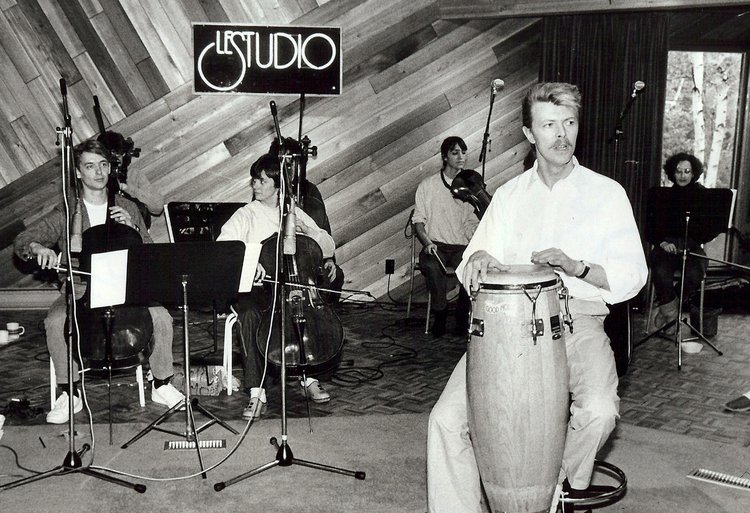

Fast forward through his turns as an in-demand studio session player, a jazz band leader, and founder of two Montreal-area studio facilities that served local talent, and we arrive in 1974. It’s the year André built Le Studio, a mythical music studio that was ground zero for so much of the great music released in the 70s and early 80s. Today, Le Studio stands gutted and abandoned, a relic of the past—a sad irony when we consider how cutting-edge it used to be.

For one, it was the only studio in North America to use the Solid State Logic Mastersystem console, considered, still today, one of the world’s finest consoles. Only one other existed at the time, at London’s Abbey Road Studios. Le Studio also introduced the digital recorder, first used on The Police’s Synchronicity album.

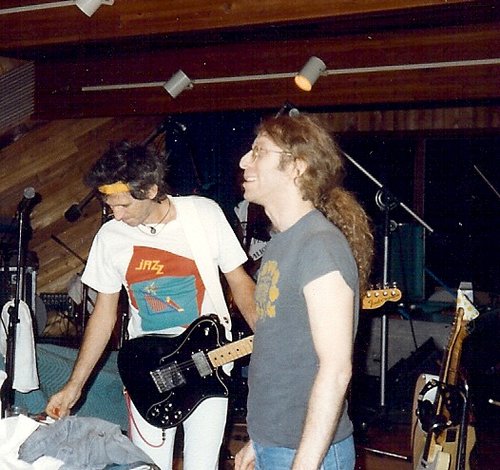

Perhaps most innovatively, Le Studio wasn’t located in any urban area. Far from it—literally. It was tucked in the Laurentian mountains of Morin Heights, deep in the woods, about 65km from Montreal—far from the noisy bluster of city life and the mechanics of business. It was in this cutting edge compound entrenched in nature that some of the world’s most famous artists and producers would embed themselves, sometimes for months at a time, to create the next big record, and many of them did just that. The 100 or so albums recorded at Le Studio have generated combined sales of over 330 million copies, and those are just the legal ones.

However, being isolated in the woods isn’t everything. “It’s not because it looks beautiful outside that it’s going to bring the hits,” André tells me. “Music comes from inside the artists. From the soul. But our place had a vibe. We had a few groups that came and walked inside the hallway and saw these Platinum records on the walls and thought the magic was going to rub off on them. People had a tendency to think that because Le Studio was chic, comfortable, and had a great chef, that was the trick to success. It wasn’t that. The artists worked very hard. They would come to the studio around noon and work until 2am. There was big money involved. We had acts that paid for 6 months. We had to turn down all kinds of people, including Elton John, because we had three groups booked for a year and a half.

“People felt good at our studio, but that didn’t necessarily mean they were going to come out with a great record, just that the conditions were good. Le Studio was first to make use of plenty of glass which was considered taboo in acoustics at the time. We had large windows between the control room and studio, which created a new intimacy between the engineer, producer, and the musicians. We had wall-to-wall, floor-to-ceiling windows looking out on to nature and a lake. There were curtains but they were only drawn once. This area in the studio became the ‘live’ part of the room and was sometimes used for drums—such as in the case of Rush—and for the string section for David Bowie.

“We were also one of the first studios to draw artists from around the world, the reason being that we were not associated with a particular sound or culture. Studios from Muscle Shoals, Nashville, L.A., N.Y., Chicago, London, etc. were mainly sought out for their particular sound. Also, our staff came from everywhere. It was like the United Nations, with engineers from the U.K., Canada, L.A., N.Y., which allowed us to blend into various cultures.

“We didn’t have a sound, we had all the sounds. If you listen to the 100 albums that were recorded there, you’ll find that they all sound different. The Bee Gees have a Miami sound, Rush has another sound, so does Wilson Pickett, and Chicago. That’s because I always looked at the studio equipment not as equipment, but as an instrument. We would tune the studio to suit the artist. The Bee Gees did the overdubs at Le Studio, then wanted to go to Miami to do the mix so they could get the Miami sound. So, during the night, we retuned the whole studio—all the equipment, the echo chambers—to give the Bee Gees the Miami sound. We mixed one track at 7 in the morning. When the group showed up later, we played it for them and they said, ‘F–k that! We’re finishing the album here.

“We made the studio an international head space recording facility. We were avant-garde. And it’s hard today to find that same recipe.”

I ask André what his relationship was like with the artists. “Like I said, most of the studios were owned by major labels, which made the relationship between the artists and the studio more commercial,” André says. “But I was one of the guys. I was a musician. I was an engineer. I was a producer. When they came to André’s place, the rapport that they had with me wasn’t like with the guy who owns a studio and sells studio time by the hour. Cat Stevens came and did his first record with us, got to know my wife and me, and he wrote a song for us, “Two Fine People”. Rush did eight albums with us. So when they came, it was family. It was André’s place. It wasn’t a commercial place. And the artists owned it while they were there. So, of course you can’t compare it to a standard type studio in a big city.”

Did he find the artists, or did they find him? “There was no need to find them. Let me throw a number out. It’s not precise but it’ll give you an idea of the scope. At the time, the international recording community was about 2000 people who knew each other. That included management, record companies, and artists. Whether you liked it or not, this was a private club. So, in our case, it started with Cat Stevens who had just broken up with his girlfriend and was looking to isolate himself for his next project. But he didn’t like working in city studios. He heard that we had a studio in the middle of the woods, so he gave me a call and said he wanted to try our studio for four days. He stayed four months and recorded three albums.

“After Cat Stevens, the word went out and, luckily, the artists that followed brought us the quality content and the hits. Before we knew it we had the Bee Gees, Brian Adams, Rush, Chicago, The Police, Asia, etc. But you have to deliver.

“We were always taking chances, being motivated to be the first at anything. Unlike now, at that time you could strive for having the edge on the competition. I was hanging out with the guys at Solid State Logic, helping to develop new features in their consoles. When you listen to recordings that were done in that period, a lot of the colors and effects were created by using the console in combination with the instrument. Musicians would often do their overdubs while sitting in the control room with the producer and engineer.”

Did he use compression—that common studio technique of shaving off the extended frequencies to make the music sound louder? “Of course we used compression because it was a pop market. The music had to pop out of your radio. But the amount of it depended on the record. Listen to Rush’s Moving Pictures and you won’t hear it because we used very little.”

I ask what he thought of CD sound at first. “I haaated it. I haaated it. Because the first thing I missed was the second harmonic. And since I always had a sound system that was a bit warm, I missed that 2nd order harmonic.”

Were any of the artists problematic? “Only one,” says André. “But I solved that in a sweet way. I don’t want to mention his name because it won’t serve a purpose. But he made a big scene because he thought our staff had stolen his wallet. And a couple of days later, the dry cleaner called and told him they’d found his wallet in the pants he’d sent to them.

“So I went to an art gallery in Montreal and bought a beautiful art piece. I brought it to him and said, ‘You know, we’re just not like that. You’re not in New York, not in L.A., and it’s not the way we are.’ And he stayed and finished the album. But that was about it. There wasn’t any trashing or breaking stuff.”

“So no fist fights?” I ask.

“No, no.”

“I heard the neighbour found a drum cymbal in the lake next to you. Any idea how it ended up there?”

“(laughs) That must have been Rush,” André says. “I had an idea one day to take a picture of the drums on a floating dock. If the neighbour found a cymbal in the water, it probably fell in and nobody wanted to go get it (laughs).”

Did he ever offer creative suggestions to the bands? “It depends. Because at the level that those guys were at and the careers that they were having, it would have been very delicate to do that. Maybe I’d do it through the engineers, who reported to me on the sessions. Maybe if it came to the sound, or the recording process, I would put my 2¢ worth. But I would not intervene during the group’s session. I don’t see how that would have been justifiable.”

“So no creative disagreements with any of the artists?” I ask.

“No, because the kind of producer I am is to work around the artists and make the magic happen. Yes, there were tense moments, but they were between themselves. Any time you’re dealing with creativity, you’re bound to get into disagreements. And then there were groups that were so smooth. Rush. Nazareth. They were darlings. Chicago, too, who were really two groups, because they had a horn section and a rhythm section and they would record separately. They both had their own sense of humour and would crack jokes. They were a lot of fun.”

Considering the company he kept, did André ever get star struck? “No, no, no. I’m a jazz guy, man. Jazz guys don’t get nervous. No, we were professionals. We showed up and did the work.“

*I’d like to thank André’s wife, Yaël Brandeis Perry, for her invaluable help in making this interview happen.